Insider Feature: KEF

At 56 years old (and counting), KEF is one of the elder statesmen of the loudspeaker industry. What is notable about the Kent-based company is that it has never been content to plough a particular furrow, and the ‘Innovators in Sound’ slogan that adorns the wall of the acoustics department is rather more than just marketing puff.

In fact, innovation is the reason why KEF came into being in the first place. Company founder Raymond Cooke had worked for the BBC and Wharfedale prior to founding KEF in 1961. The company initially began operations from a Nissen hut on the site of Kent Engineering & Foundry in Maidstone – where the KEF name was first formed.

From the outset, Cooke used the foundry to produce components for his speakers and before too long had acquired the entire site. The original hut survived until comparatively recently, but as it was growing increasingly dishevelled and filled with asbestos, it was pulled down and KEF makes do with a model of the building for reminiscing purposes.

Cooke’s radical and innovative driver designs quickly found acclaim and by the late sixties the company was a major player in the speaker business, helped in no small part by Cooke taking a very hands on view towards exporting his product. By the time KEF produced the original BBC LS3/5a monitor, it had cemented a reputation for intelligent design practices coupled with clever material choices. While the LS3/5a was made by a variety of companies, all official versions used KEF drivers.

These innovations continued throughout the seventies and eighties and processes began to evolve that shape how KEF designs speakers to this day. It was one of the earliest proponents of computer modelling, using it for some aspects of design as early as the seventies and as computing power has increased, so too has the scope of what KEF has attempted to do with it. What began as a means of measuring responses more accurately has become one of the most sophisticated processes in the industry.

Head of acoustics Dr Jack Oclee-Brown has been one of the driving forces behind this shift. The software that KEF uses was written by him and it has developed in both functionality and accuracy over the years. It can now begin with demonstrating the notional feasibility of a product – what the penalties and challenges of an ultra slim cabinet might be, for example – and then go on to accurately model where drivers and ports would need to be placed for best results. From there, refinements can be progressively modelled into the design – port length and shape, crossover types and internal volume can all be set and the data examined with impressive accuracy before a single component actually exists.

Model behaviour If the product is deemed to be viable, the next phase of modelling can take place. This examines the behaviour of the drivers across an enormous frequency range and will point out any issues with dispersion and break up in a manner that would have been pretty much impossible at the turn of the century. The study and management of this behaviour has particular relevance to KEF because of its use of the ‘Uni-Q’ driver concept, which sits the tweeter in the centre of the midrange driver. The benefits of doing this are clear, but realising those benefits has been made considerably easier thanks to these modelling processes that have led to refinements like the ‘tangerine’ waveguide now used across the ranges.

Oclee-Brown is keen to stress that while the computer modelling is an integral part of the design process that KEF employs, it hasn’t replaced the human ear as the final arbiter of product performance. In fact, the process of listening to prototypes can highlight information that is present in the computer model, but that only reveals itself when the right questions are asked. Combined with rapid prototyping, KEF can now develop products much faster and with considerably less trial and error than would have been the case previously. As well as the computer modelling, the company retains the use of an anechoic chamber and a larger acoustic space where measurements can be performed – although the team is not averse to using the car park when required.

The acoustics team works closely with a mechanical design staff. This partnership ensures that the designs that come to fruition virtually can then be assembled in reality and from the best materials for the job. This becomes particularly relevant when you take into account the fact that the majority of KEF’s manufacturing – including all of the drivers – takes place in the Far East.

With the large distances involved, it is vital that each speaker design becomes a carefully realised set of components that will come together in a logical and expected way before manufacturing commences. With some of the more advanced shapes in the KEF range – everything from the EGG to the Blade – the ability to produce a 3D model of the design instead of an old 2D blueprint is the difference between these designs being feasible and remaining a pipe dream.

KEF is owned by GP Acoustics, which is a member of Hong Kong-based Gold Peak Group and uses its own factory to produce items to make the construction process simpler. The final assembly for all its Reference, Blade and Muon models is still done in Maidstone. The drivers from overseas arrive having been grouped on measured performance to ensure that they will work well together. There is a small anechoic test chamber that can be used to check any speaker against an engineering reference allowing for quick and relatively seamless checking for the smallest of issues. Once checked, the process of final assembly can take place.

One man army

What is notable about this is that the process doesn’t work as a production line. A technician will be given a build sheet and assembles whatever speaker is detailed on the sheet. There isn’t a ‘hand off’ from one station to another to perform different processes, and one technician will perform the entire build at their workstation. As you might expect, with expensive and heavy cabinets that need careful handling, no rings or watches are worn on the production floor and each speaker is microscopically inspected before being signed off. Quality control Not all of the tests are visual. Once again, KEF’s expertise with software is used to good effect for quality control. Each finished speaker is placed in a test chamber and its performance measured against the engineering reference of that particular model. The test microphone is sufficiently sensitive that it is able to determine if the door to the chamber isn’t closed properly and it allows for quick and effective checks to be run on everything before it leaves the factory. These tests are then run alongside a more human-based rattle and connection check. Finally, the test results of each loudspeaker are logged and retained in case the owner has any questions about their acquisition further down the line.

Of course, the Reference, Blade and Muon represent only a tiny part of what KEF does and you only need to spend time in the showroom to realise this. While conventional box speakers are still a significant part of its business, the category is a mature one and while KEF has increased sales in recent years, it is actively looking at new categories as the major source of growth. While they don’t feature that often in the UK market, in-wall and in-ceiling speakers have become a major area of development and it produces models up to and including Reference spec for stereo and multi-channel configurations. KEF has recently moved into what it calls the high-quality lifestyle sector – self-contained products offering high performance and flexible specifications. Models like its LS50 Wireless (HFC 433) are part of this considered move into this growing area as consumers seek out ever more versatile and sophisticated one-box music solutions. KEF feels that this offers the best opportunity to demonstrate its expertise in design and engineering while moving the company forward into new markets.

This is partnered with an equally determined move into the portable audio product sector. Competition here is significant, of course, but its models here brings the KEF brand to the attention of new customers who are then likely to explore what the company is doing in other areas at a later date.

Natural selection

It’s a crowded sector, but where KEF differs from many of its rivals is that the changes it is undertaking feel more natural, as it has been innovating from the outset. Some products may have altered beyond all recognition, but the distinctive design approach and relentless attention to detail is as apparent now as it has always been. The shape of audio systems is continually evolving, and KEF looks well placed to continue to play a big part in its future.

Read the full feature in March 2018 issue 434

|

Inside this month's issue:

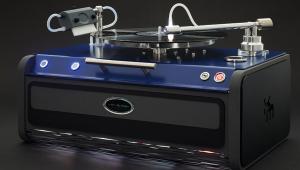

Q Acoustics 3020c standmount loudspeakers, Perlisten R10s active subwoofer, Quad 33 and 303 pre/power amps, Acoustic Solid Vintage Full Exclusive turntable, newcomer Fell Audio Fell Amp and Fell Disc and lots, lots more...

|